(This post originally appeared June, 2013).

There are many ways to organize a narrative essay. No real rules or formulaic outlines exist, which appeals to many writers. This can also cause a lot of frustration for the writer who is used to rules and outlines. The flexibility of form of the narrative essay gives the writer the freedom to tell his or her story as creatively as he or she chooses. What we suggest here are only general guidelines. As you compose your essay, consider the story you want to tell and which form works best to communicate that event.

Ingredients

What goes into a narrative? Traditionally, if you are going to retell an event, you’ll need to include three elements: Scene, Summary, and Reflection.

Scene is action. People are talking (dialogue); you or other people are moving or reacting to something.

Summary is exposition. It is condensing time (making a long stretch of time shorter) or conflating time (making a short stretch of time longer for dramatic effect). Summary can be history and background, filling in the blanks for the reader.

Reflection is your – the narrator’s – thoughts. What did you think or feel as the action was happening? What do you think or feel now? How have you made sense of what happened? This is reflection.

These three elements do not necessarily have to be in equal increments. This is a writer’s creative choice on how much the writer feels is necessary to fully communicate his or her story.

The Intro

Literature is filled great “hooks” or opening lines: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Anna Karenina

“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times. . .” A Tale of Two Cities

“Call me Ishmael.” Moby Dick

And this line, probably the most famous (and now most clichéd): “It was a dark and stormy night.” Paul Clifford

Composing an engaging hook, or opening line, is essential to immediately draw your readers into your story. Without a strong intro, a reader may disengage and not continue reading, so spend some time on your intro and hook your readers before moving on.

Organization

You’ve hooked your reader, so now where do you go? Chronological organization, or retelling your story in the order events happened in real life, is one way. However, beginning writers often get stuck spinning their wheels, or spending too much time setting up a story with inconsequential exposition, which runs the risk of losing your readers.

Beginning in the Middle

Consider taking your story out of chronological order, and begin in medias res, Latin for in the midst of things. In an in medias res narrative, the story opens in the middle of the actual chronology of events, usually with dramatic action rather than exposition setting up the narrative. The story begins in the middle, moves forward from there, with the past told in flashbacks. An in media res intro works well to hook the reader, as the dramatic action begins immediately.

Once you begin composing your narrative and you’ve decided on how you are going to organize your event, you’ll now need to put it all into paragraph structure. Narrative essays don’t have the type of topic sentences that an academic paper has or obvious signals on when to begin a new paragraph.

Obvious paragraph breaks will be when speakers change: new speaker = new paragraph. Other breaks may not be so obvious. Think in terms of the action, and structure the paragraphs around the action. Generally, narrative paragraphs change when something in the action changes:

Introduction of new people

Location or setting changes

Time passes or era changes

Action changes

Mode changes (action changes to reflection, reflection changes to exposition)

Climactic Moment

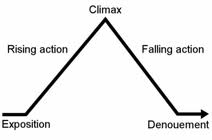

For a narrative event essay, you’ll probably be asked to consider the narrative arc, or the climatic sequence of events. When you decided on what event to retell, you most likely thought of the “climax,” the high point of excitement or the turning point of the event or experience. But to retell this event and to get to the climax, you’ll also include rising action (events before the climax) and falling action (events after the climax). Many writers find it easier to work backward, or write out the climax and work up to that point. It doesn’t really matter how you get there, just that you get there.

Narrative Arcs aren’t necessarily a perfect arc

Even in the shortest narrative event essays, you’ll need to include the basic elements of plot to complete your narrative arc:

- Exposition

- Rising Action

- Climax

- Falling Action

- Resolution

(Denouement is a French term meaning resolution)

However, don’t assume that because the “climax” falls in the middle . . . that it falls in the middle.

The climax to a narrative can often be closest to the conclusion of the essay, followed by a brief resolution or denouement.

Conclusions

Many writers find the conclusion, or resolution, to be the most difficult part of the narrative to write well. Try to avoid the inclination to overwrite the conclusion. The central meaning, or universal theme, should be apparent in the narrative. If you have to tell the reader what it all means in the end, you might need to go back and expand the narrative so readers can derive meaning as they see the story unfold.

As you can see, writing a narrative essay is no easy-peasy-lemon-squeezy writing assignment. It takes a lot of thought and planning.

On the other hand, don’t over-analyze how you should organize your narrative so much that you get analysis paralysis. Sometimes, just sitting down and writing as if you were simply jotting down a diary entry of a memorable event will open the creative channels from which your story will effortlessly flow.

Not likely, but that’s what revision is for.