Narrative or Personal Essays are a common writing assignment in English classrooms. Many freshman will run across this type of writing in college, and for natural storytellers, it can be a fun assignment. If the guidelines ask you to simply retell an event from your past, you already know the information! For a narrative essay, most likely, no research is required. Composing a narrative is simply a matter of putting a story from your past on paper. Sounds easy, right?

Actually, not as easy as it sounds. Move ahead with caution.

One of the biggest problems that arise when composing a personal narrative is not compiling the information; you already know it, as it’s part of your memory. The problems often lie in organizing those memories into a cohesive, well-organizing, interesting story that holds the reader’s attention from start to finish. This is not always so easy.

Once Upon a Time

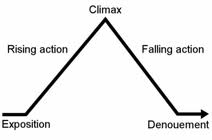

Logic would tell you that if you want to retell a story or event, you will start at the beginning and conclude at the end. Right? Not necessarily. Taking a story out of chronological order is often the most effective way to hold the reader’s attention, create rising tension, an exciting climax, and conclude with a thoughtful reflection of what it all meant to you. This is what is referred to as the “narrative arc.” This seems logical; beginning, middle, end. Sometimes these narrative essays will incorporate a brief flashback, but never deviate from the chronological retelling of events.

The problem with this kind of storytelling organization is that it can become tedious to a reader. Writers tend to begin too far back, before the actual event even begins, then proceed to tell every detail up to the conclusion. By the time the reader gets to the main event or action, he or she may lose interest. By taking the narrative out of chronological order and begin in the middle of the action, or what writers refer to as in media res, we get off to a swift start that will sustain the narrative through to the end and hook the reader’s interest.

In medias res (or medias in res) is a Latin phrase which simply means the narrative story begins at the mid-point of the action rather than at the beginning. Setting, characters, and conflict can be set up immediately via flashback, conversations, or inner reflection. The main advantage of starting in the middle of the event is to open the story with dramatic action rather than explanation (exposition) which sets up the characters and situation in an exciting and captivating story. The reader is hooked immediately; a “hook” is often a requirement of a narrative essay. Beginning in the middle of action avoids what writers refer to as spinning your wheels or throat clearing; a lot of talk that gets you nowhere.

In medias res often (though not always) entails nonlinear narrative, or non-chronological order; earlier events are condensed briefly in the backstory. Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey use this technique to begin with the action of the Trojan War. To Kill a Mockingbird begins with Jem’s broken arm, which doesn’t happen in the narrative until the conclusion. The entire Star Wars series is completely out of chronological order! Think about the stories you’ve read for class; where in the story has the action begun? I’ll bet you’ll find it is seldom in the actual beginning of events.

CUT!

When composing your own essay, there is no right technique on how to organize it, but one tool writers use once a solid draft is complete, is scissors. Print your draft on one side, and cut each paragraph into its own page. One you have all of your paragraphs cut up, lay each out in front of you. Try to envision where the narrative could be re-arranged, and play with the organization. When you chopped up your essay, did you notice a lot of paragraph breaks, or two double spaces between paragraphs (white space)? If you tend to use a lot of paragraph breaks with no discernible reason, maybe that paragraph is in the wrong place in the narrative. Place the end at the beginning. Place the beginning in the middle. If a paragraph doesn’t fit, maybe it’s not needed. Maybe you’ll find a gap in time or action that needs more information to clarify details of the event.

Once you shift your perspective to consider other possibilities of organization for your narrative other than chronological, you may find that the first two pages of your narrative are unneeded. You will hook the reader more quickly by eliminating non-essential details and placing him or her immediately into the action, which will improve the narrative arc and set you on course for a narrative essay that your reader can’t put down.