The Five Phases of Writing-Project Planning for a Stress-Free Paper

Whether you’re writing a fictional essay or an academic research paper, the beginning stages of writing can be overwhelming. Many writers struggle with initial questions such as

What topic should I choose?

What do I think about my topic?

How can I get all my jumbled thoughts to make sense?

How can these jumbled thoughts ever result in a successful essay?

“Don’t just do something. Stand there.” – Rochelle Myer

Beginning writing without spending any time in the initial planning stages is a recipe for failure. Careful planning is vital before any action can be taken. In the world of business, this is referred to as Project Management. According to business writer and coach, David Allen, author of Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-free Productivity, our minds go through five steps to accomplish any task:

- Defining purpose

- Outcome visioning

- Brainstorming

- Organizing

- Identifying next actions

Before you ever begin developing an outline for your paper, you’ll need to answer a few key questions.

What is my purpose?

If the purpose of writing is to satisfy a class assignment, what is the assignment? What are the guidelines and requirements? What type of topic can best satisfy those requirements?

This is merely common sense. Don’t get caught up in worrisome details. Think about the “why” behind why you are going to write. Knowing the why will help clarify your focus and make the rest of the decision-making process easier.

If you decide your purpose is to write a policy proposal on a current issue in your community, then knowing that will guide your choice of topic.

What outcome do I envision?

Having a clear vision provides the blueprint for your paper. Do you want to argue in favor or in opposition to a controversial issue? Do you want to propose changes to current laws, policies, or procedures? The vision is the “what” instead of the “why.”

Take some time here to imagine what you want the final paper to communicate. What arguments or points do you want to make? What message do you hope readers take away? What changes in thought or policy do you hope readers will consider?

For example, you might envision readers will agree that spending more in the city budget to increase the number of bike lanes in your town will save money in the long run by reducing road maintenance, traffic, and accidents. That is the outcome that you envision.

Brainstorming

Now that you know your purpose and where you’re going, you’ll need to capture ideas of how to get there. Following the why and the what comes the how.

“If you’re waiting to have a good idea before you have any ideas, you won’t have many.” David Allen

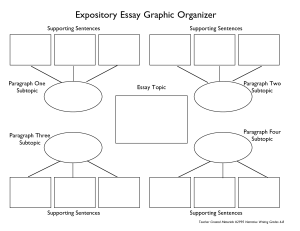

Brainstorming has lots of terms – mind-mapping, clustering, spider webbing – but they all basically mean the same thing. They are all ways to graphically organize our thoughts. Once you’ve defined your purpose and vision, your brain will automatically begin to create thoughts and ideas, but if you don’t have any method of capturing those ideas, you will either lose them – or won’t have any. Psychologists call this “distributed cognition,” or the need to get all the stuff out of our heads and into objective, reviewable formats, such as a mind map, cluster, or even a Post-It note.

“The best way to get a good idea is to get lots of ideas.” Linus Pauling

The most important thing to keep in mind is to not judge your thoughts as you have them. You are going for Quantity, not Quality. You might naturally analyze them, such as, “Here’s what might not work with that idea,” which is good. You’re beginning to critically think about your project. But don’t let your critical side overtake your creative side yet. Just give all your ideas a chance at this stage and analyze their usefulness later.

Organizing

Now you know the why, what, and how. Once you’ve emptied all the clutter in your head, your mind will naturally begin to organize those thoughts. You’ll think in relationship to sequences and priorities. What are the essential components for the final paper? Which of the brainstorming ideas will best support my argument?

Organizing is a matter of identifying the significant pieces, then sorting by

- Components

- Sequences

- Priorities

In relation to an argument paper, what are the major components needed to reach your vision? This will most likely be the major points of argument that will support your thesis or reasons why your policy proposal should be implemented.

For example, the policy proposal, increasing spending in the city budget to increase the number of bike lanes in your town will save money in the long run, will require the components of argument points, such as

- reducing road maintenance

- reducing traffic

- reducing automobile accidents

Other components might include the opposition’s side, outside research, and a call to action.

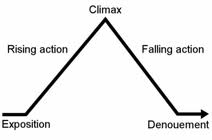

The sequences are the natural progression of the paper. How should you order the ideas – which should come first, second, and last? How will you organize the paper to best present the information for a logical flow? Should you introduce the opposition for each point, or should it come after the points are fully laid out?

Finally, what are the priorities, or essential information that must be included? What must you do first to meet these objectives? For example, once you determine your topic and brainstorm ideas, you might need to gather information from research, data or statistics. Consider what is your next step, and what steps should follow, prioritizing your work into manageable steps. Every essay is different, and no two projects are the same, so for one you might need to do more initial research before you begin, and for another, you might need to write out the points of opposition first.

Identifying Next Actions

So far, you’ve considered the why, what, and how, and begun the steps to organize how you are going to approach the work, prioritizing your next steps. The final stage of planning your writing project should come easily once you’ve defined and clarified your project.

Any writing project, especially longer projects, will have lots of moving parts. For each step above, decide what the “next action” is for each moving part of the project. For example, if you know your paper’s thesis, but not quite sure on your major points of argument, your next “action” might be to brainstorm a bit more to decide on your points of argument. If the components of your essay will require quotes from experts, your next “action” will be to locate research from reliable resources. This will most likely require you to find library databases with peer-reviewed research, read lots of articles, and begin keeping notes on source information that will best support your essay.

Make A Plan!

As you can see, a lot of planning goes into a writing project before the actual writing begins. How much planning is enough? As much as you need to get the project off your mind. The reason things are on your mind and causing you worry is that the outcome and action steps have not been clearly defined, or you may not have developed the details sufficiently to trust your plan. If you are worrying about the project, you obviously need to spend more time planning.

Feeling confused or lack clarity? You need more planning in stages 1, 2 or 3. Are you getting bogged down in research? Do you need more action? Move down to steps 4 or 5. You don’t need to read every single article on your topic in EBSCO to collect 6 or 8 required sources for your project. Focus on what you need that will meet your objectives, and move out of the research phase and onto writing.

Applying project management steps in your writing will not only save you time in the end, but will also create a mental environment where worry, stress and anxiety will be reduced, allowing creative ideas to flourish, one step at a time.