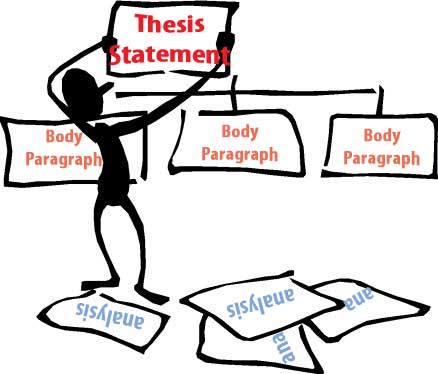

Writing an essay is like constructing a building. A blueprint offers a builder guidelines to help erect a building. A writer requires the blueprint of a focused thesis to guide his or her paper to completion. Without a strong, focused thesis statement, a paper may lack the solid structure it requires to maintain a logical argument through to the end.

Once you have decided on a topic, ask yourself the big “SO WHAT?” What do you want to say about your topic? What is your opinion? This questions trips up many students who don’t feel they should have a strong opinion on a subject. Many writers prefer to ride the fence, or stay safely in the middle of an argument. That won’t work with a thesis statement. In fact, a thesis should be a statement of opinion that someone would disagree with. If there is no possibility of disagreement, the thesis needs more questioning.

Revising Thesis Statements

Maybe you have an idea what you want to write about, but don’t really know what direction to take. Forming the idea into a research question will begin paving the road to the thesis.

Say you have a passion for the environment. After doing some initial research, you are curious as to why, with all our current legislation, greenhouse gas emissions are still on the rise. So you might form a question something like this:

Research Question: Why are greenhouse gas emissions still on the rise?

This isn’t a thesis yet, but it’s on its way. A thesis statement must be a declarative sentence, or a sentence that declares something in the form of an opinion. A thesis cannot be a question, as there is no opinion in a question. However, if you have a question, a thesis could be the answer to that question, but only if it creates disagreement.

The following example takes the research question and forms a declarative statement:

Non-debatable Thesis: Greenhouse gas emissions are bad for the environment.

This thesis statement is not debatable, as it’s an obvious fact that greenhouse gas emissions are bad for the environment. No one would argue pollution is good, right? Saying greenhouse gas emissions are bad for the environment is like saying smoking is bad for your health, again, a proven fact. It cannot be debated, so there is no argument to pursue, and therefore, no thesis.

Often it helps to narrow the focus the thesis so it isn’t so broad. Consider how we might make this more specific:

Non-debatable Thesis: One of the major causes in the rise in greenhouse gas emissions is international transportation.

This is an interesting fact, but, alas, still a fact. I would like to know more about international transportation and its effect on the environment, but this isn’t quite a thesis statement yet. It’s non-debatable because this fact can be looked up in research and found to be true, so not yet an arguable thesis.

You could rework the topic to focus on how we might prevent greenhouse gas emissions:

Arguable Thesis: The US should focus anti-pollution legislation on ocean and air transport, or international transportation, one of the fastest growing source of greenhouse gas emissions.

This is a thesis that is arguable and makes a declarative statement. It is strong and succinct. The best part is that this thesis is unique, one you (or your instructor) probably haven’t read about. The instructor will approach it with fresh eyes and mind, as opposed to a paper on why we should lower the drinking age, a tired, worn out topic.

Beware of Feelings over Facts

Often we become so passionate about a topic that it’s difficult to separate our feelings from fact.

Personal Feelings Thesis: The songs of rock group Post & Stone relate to the feelings of individuals who dare to be different, and are meaningful to me because I can identify with them.

You can’t compose a thesis statement based on personal feelings, as they will never hold up in an argument. But, you ask, isn’t a thesis supposed to be your opinion? Yes, but this thesis has no real argument, as an audience can’t disagree with whether or not music is meaningful to another person.

So how might you rephrase this topic into an arguable thesis? In the previous examples, we needed to narrow the focus to create an arguable thesis. However, this thesis is too narrow, and it will be difficult to keep it focused on one musical group, so consider how you might broaden the scope.

As you read more, you’ll find that music therapy is a popular form of psychotherapy. It’s also shown to be effective in dementia patients. If you want to keep the focus on music, consider the following:

Arguable Thesis: As music therapy has been proven to alleviate post-traumatic stress disorder and depression, military psychologists should include music therapy in veterans’ treatment.

Arguable Thesis: To decrease medication use, lower costs, and improve patient recovery times, music therapy should be standard practice in all hospitals.

These are both workable thesis statements, and you can see how they will guide each paper. The first will focus on military only, although you could certainly tweak for different sub-group; the second thesis will show how music therapy decreases the need for medication, decreases hospital costs, and speeds recovery times in hospital patients.

Once you’ve done some initial research, you can always tweak the thesis statement. When you have your blueprint in place, building the essay will be much easier than attempting to construct an essay on a faulty foundation.

Thesis Practice

- Revise each of the thesis statements below to create an arguable thesis.

- There are positive and negative aspects of legalizing marijuana.

- This paper will be about the health benefits of exercise in children.

- Fashion magazines have no right arbitrarily to define standards of “beauty,” which often lead to eating disorders.

- Body piercing is popular among kids today.