When choosing a topic for your argument essay, it’s always best to choose an issue that you’re interested in and passionate about. There’s nothing worse than spending an entire term researching and writing about something that you have little interest in. But it’s also just as important to be fair and unbiased as you write your essay. The language you choose to communicate your points can work to either persuade – or alienate – your audience.

While it’s okay to feel excited or even enraged about a topic, your audience requires careful respect and consideration. Too much wrath and fury, or on the other side, too much praise and approval, will cause your reader to doubt your reliability, and could turn your audience against you.

Avoid Moralistic Language

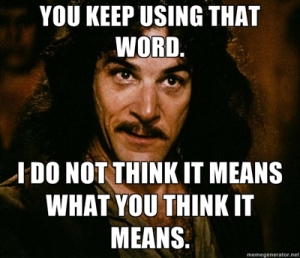

A fine line exists between persuasive and opinionated, and it all comes down to word choice. In order for readers to feel sympathetic toward your position, a balance must be struck. In the example below, consider how your reader will react:

An added tax should be placed on all surgery drinks, including sodas, and is the only way to encourage healthy alternatives.

At first glance, many health-conscious readers might think this is a good idea. Added federal and state taxes are placed on another unhealthy – though popular – product, cigarettes, so why not sugary drinks?

But this statement implies that all surgery drinks harm our health. Most fruit juices, however, have as much, if not more, sugar than a can of Coke! But some fruit juices have no sugar added; the sugar content comes naturally from the fruit. Are fruit juices high in sugar? Yes. Is fruit juice as harmful as soda? Many would heartily disagree, and juice-drinking readers might feel targeted.

Avoid Superlatives and Exaggerations

Note the use of “only way” in the above example. The phrase, “is the only way to encourage healthy alternatives” implies that higher taxation will automatically push consumers to choose healthier options. The language of “the only way. . .” is a superlative that might turn off a reader by the moralistic tone. It could be one way, but not necessarily the only way.

Superlatives are terms that suggest the highest degree of something, such as

the best way

the worst way

should always

should never

Using superlatives paints the writer into an absolute corner and has no room for compromise.

Alternative: An added tax should be placed on all surgery drinks, including sodas, and could be one way to encourage healthy alternatives.

Example: Legalizing marijuana is the best way to decrease prison overcrowding.

Alternative: Legalizing marijuana might be one way to decrease prison overcrowding.

Example: Embryonic cell research is the perfect solution for finding a cure for Alzheimer’s.

Alternative: Embryonic cell research is one of the best options to find a cure for Alzheimer’s.

Notice the difference in tone? Superlatives and exaggerations come off as dramatic and often biased and opinionated. By simply changing the language, your reader will be more apt to consider your points and consider your position as credible, whether or not they agree with you in the end.

When constructing an argument, consider how your language might be interpreted by varying audiences. While those who agree might not be offended, neutral or opposing audiences might be turned off by the language and opinionated tone.